Tarpon Springs, Florida, once known as the nation’s sponge-fishing capital, today boasts a new designation: the first city in the country to declare itself a trauma-informed community.

It isn’t that the 24,000 residents of the scenic Gulf Coast town know more than the rest of us about emergency room techniques, spend their time crunching spreadsheets of violence data or watch more episodes of “America’s Most Wanted.”

Being a trauma-informed community means that Tarpon Spring has made a commitment to engage people from all sectors—education, juvenile justice, faith, housing, health care and business—in common goals. The first is to understand how personal adversity affects the community’s well being. The second is to institute resilience-building practices so that people, organizations and systems no longer traumatize already traumatized people and instead contribute to building a healthy community.

Beginnings: a goal to stop violence

The journey officially began in February 2011, when the Tarpon Springs City Council signed a memorandum of understanding to marshal the community to address and prevent childhood and adult trauma.

The results have been profound. Trauma-informed practices have been implemented in small and large ways in a variety of organizations, including an elementary school, an ex-offender re-entry program and the local housing authority. The Pinellas County Department of Health recently decided to incorporate in its Community Health Improvement Plan a goal of providing trauma-informed information in all of its county health facilities.

“Once you bring the community into it, you just don’t know how it’s going to grow,” says local artist Robin Saenger.

“She listened,” says Saenger, “and then said: ‘You’re talking about a trauma-informed community.’” Blanch explained how many of the issues facing Tarpon Springs—homelessness, domestic violence and substance abuse—stemmed from childhood adversity. And the Peace4Tarpon Trauma-Informed Community Initiative was born.

“My belief is that trauma is universal,” says Saenger. “Everyone’s experienced trauma in one form or another, and usually does on a regular basis throughout the course of a lifetime,” whether that stems from being in a car accident, witnessing domestic violence or having a loved one with substance abuse problems. And everyone is affected

by the consequences of that trauma, including the cost of emergency health and social services, school dropout rates, local violence, and absenteeism on the job.

So, how did the people in this city embrace such a radical concept in such a short time? “The nickel dropped” for Mayor David Archie and the board of commissioners on the day in 2010 that Blanch did a presentation about the CDC’s ACE Study and trauma-informed care, says Saenger.

“I could tell that [the mayor] completely grasped the concept, and as a city leader, was in a position to do something about it. He’s also director of Citizens Alliance for Progress, a neighborhood family center, and he realized that trauma is the root cause behind many of the challenges faced by neighborhood residents.”

Saenger met with the police chief and city manager to talk about what Tarpon Springs was doing right and where it could use some help. They put together a list of 30 people they thought would be interested in the Peace4Tarpon initiative. This group met and formed a steering committee that includes representatives from churches, the school district, the library, St. Petersburg College and the Juvenile Welfare Board. It also includes the police chief, the mayor, the city manager, directors of the community health center and the housing authority, the sheriff department’s ex-offender program and a growing number of community members.

In early 2011, the local Rotary Club held a community education day and chose trauma as the topic. Six days later, as a result of the steering committee’s work, a memorandum of understanding was signed by the Tarpon Springs Community Trauma Informed Community Initiative to, among other things, “increase awareness of issues facing members of our community who have been traumatized to promote healing.”

_________________________

For the last three years, four subcommittees—community action, health and wellness, children’s initiative and social marketing—have met regularly to move the Peace4Tarpon initiative ahead, inch by inch. An education committee was added recently; ad hoc committees take on short-term projects.

Early adopters: housing authority and schools

The biggest changes have occurred in a local housing authority and the local elementary school. Pat Weber, a longtime community organizer and executive director of the Tarpon Springs Housing Authority, was at the Tarpon Springs City Council meeting when Blanch and Saenger presented the ACE Study. “It was just incredible to me,” Weber recalls. “I said to myself: ‘Well there’s the proof.’ When [Saenger] said, ‘We need to do something,’ I said, ‘I’m in!’”

Weber had already coached her staff members, who manage 225 units of public housing, to think about people as people instead of as problems. “They don’t keep their house messy because they want to have cockroaches,” she tells them. “There’s a reason for everything. In our housing authority, it’s trauma.”

The housing authority already had a long-time partnership with the local police department. Together, they’d turned a former church into a community center for the Cops ‘n Kids program, which serves 75 kids. An officer is assigned full-time to the center, and the housing authority provides staff to develop programs. The center is open after school until 6:30 p.m. and all day during the summer. “For the kids, this center and those people are like their family,” says Weber. And although the police department isn’t yet trauma-informed, the police chief attends the Peace4Tarpon meetings and sends officers to the trainings.

As a result of being involved with Peace4Tarpon, Weber provided training for her staff—a workshop called “Why Are You Yelling At Me When I’m Only Trying To Help You?” Now, she says her agency is much more tenant-supportive.

When the Suncoast Center, which provides mental health, child and family services, wanted to open a North County branch in Tarpon Springs, Weber volunteered two apartments. She doesn’t charge rent; in exchange, one of their therapists meets with a group from the Cops ‘n Kids program two or three times a week. Adults and children who live in the apartments also have access to free or low-cost counseling from one of the eight Suncoast therapists on location. The agency has a home visiting program and provides parenting training.

________________________

St. Petersburg College, also a member of Peace4Tarpon, provides tutors for kids in the housing authority. And the local 4H organization, also a member, is planning to work with apartment residents to plant a large garden. “All this is happening because they understand what ACEs are and the importance of doing something about it,” says Weber. “Three years ago, that wasn’t there.”

Most of the children who attend Tarpon Springs Elementary School have family incomes close to the federal poverty level; many live in public housing nearby. The school began its trauma-informed approach by asking students and families what they needed. The answers were basic: uniforms, eye exams, food. Through Peace4Tarpon, the school now has a uniform bank. Kids receive regular hearing and eye exams, free eyeglasses, weekend snacks, a meals program and transportation to school events.

“The community knows that if kids are worried about things, they’re not going to be able to focus on learning,” says Wendy Sedlacek, chair of Peace4Tarpon’s children’s initiative subcommittee. She’s also the family and community relations coordinator for the Pinellas County Public Schools Office of Strategic Partnerships. When teachers participated in a three-hour poverty workshop, she said, “they examined the types of trauma that poverty can cause on multiple levels. In their breakout sessions, teachers were put together as a family, with people playing different roles. Every fifteen minutes, something changed in their lives, and they had to figure out how to survive. It was very enlightening. They learned there are a lot of choices that people make that are traumatic, because there’s no other choice.”

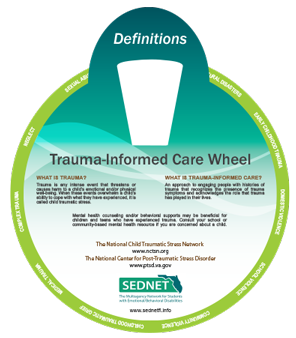

That workshop and a “trauma-informed care wheel” have provided teachers with a better understanding of different types of trauma, the symptoms and behaviors kids may express as a result, and how those traumas may be triggered in the classroom.

That workshop and a “trauma-informed care wheel” have provided teachers with a better understanding of different types of trauma, the symptoms and behaviors kids may express as a result, and how those traumas may be triggered in the classroom.

Peace4Tarpon put together a guide of community resources for families—everything from food banks to help moving belongings from one home to another. The Tarpon Springs city manager encourages all city employees to volunteer as mentors or tutors at the school, just a block from City Hall.

During this school year, Peace4Tarpon community members, parents and school staff—all trained in community support—visited families twice in their homes. They asked questions such as, “Do you feel comfortable about the educational experience your child is receiving? Does your child need a desk? A mentor? In what other ways can we support you?”

Unfortunately, the principal and vice-principal at Tarpon Springs Elementary left at the end of the school year, and “we’re starting all over again” in educating a new principal, says Saenger.

Many other pieces of Peace4Tarpon

Peace4Tarpon has made a difference in other ways:

- After the Pinellas Ex-offender Re-entry Coalition screened participants in its support groups for ACEs, Denise Hughes-Conlon, outpatient clinical director, changed the curriculum for the women’s groups to Seeking Safety, which specifically addresses trauma. The women learn information that they can use daily, such as how to say no and how to create everyday boundaries.

- Wells Fargo Bank plans to sponsor a financial literacy program for people in public housing, something Saenger sees as vital, because “financial health is often a reflection of someone’s trauma history.”

- Judge Kimberly Todd is interested in having Peace4Tarpon provide assistance on developing community service diversion programs for youth offenders.

- Peace4Tarpon co-sponsored “Being a Better Bystander” training for Tarpon Springs residents to educate them on how to safely help someone who is experiencing domestic violence or child abuse. “Last year in Pinellas County, there were thirteen domestic violence homicides,” says Saenger. “What was brought to light was that, in every case, people knew” about the problems before they escalated to murder. It’s also sponsoring monthly training for community members about child sex abuse.

- The Pinellas County Department of Health is working with Saenger to facilitate three grand rounds for physicians. For the first one — for pediatricians at All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburgh — Saenger recruited Dr. Nancy Hardt, who has taught students at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville about ACEs research.

- Two Peace4Tarpon partners who are licensed mental health counselors participate in the Give an Hour program to provide free counseling for military veterans.

- Tarpon Springs was selected as a finalist in the 2014 All-American City Awards hosted by the National Civic League, partly based on the work of Peace4Tarpon

Mostly, Saenger says, people are talking, doing presentations and increasing awareness about ACEs and resilience. “We tell people to bring what peace/piece you can to Peace4Tarpon. We want to empower people to do something, without having them think that they have to solve all the violence in the world.”

She points out that all accomplishments to date have been done without a large grant. In fact, she thinks a big pot of money—or a top-down countywide initiative—would have killed Peace4Tarpon. “You don’t throw too much fertilizer on a new plant,” she says. “And you have to grow this from the ground up.”

Not everyone jumped on the trauma-informed bandwagon immediately. For example, a local principal who attended a few early steering committee meetings didn’t see the initiative as particularly useful, telling Saenger, “We don’t have that issue at our school.”

Saenger’s response? “There’s a saying: It’s rude to awaken someone who’s sleeping,” meaning that people will come to understanding in their own time. “I’ve seen over and over that when people ‘get it,’ they become passionate and engaged partners almost immediately. They see the promise and power of this initiative.”

A few months ago, that principal sent a school staff member to a Peace4Tarpon meeting.

The stop-and-start nature of change

Saenger is patient with the start-and-stop nature of change, and she has sensed a new kind of compassion moving through the community. She tells a story about a young local man who burned down his uncle’s pawn and gun shop, then went home and killed his uncle (with whom he lived), his uncle’s girlfriend, his grandmother and finally himself.

“Rather than going into attack mode on the young man, people asked other questions,” she says, focusing on the likelihood of his traumatic history, why he was living with his uncle instead of his parents and how the community had not noticed his growing dysfunction. “People were asking ‘Where did we miss the boat?’ and ‘What happened to him?’ instead of ‘What’s wrong with him?’”

In just three years, Peace4Tarpon has become an integral part of the community. Monthly steering committee meetings are open to anyone. About half of the 60 members of the committee show up each time. “It’s never the same 30,” says Saenger. “and that works out fine.”

At the beginning, participants were mostly community leaders. “Now a lot more residents are getting involved,” she says. “It’s an interesting shift…It’s what we’re going for, but watching it evolve is interesting. It’s just so messy. It’s not a straight line. It’s not something that can be mandated and it’s not always a comfortable path, but it’s about the process, and that’s where the juice is.

“I’ve noticed that a lot of trauma-informed approaches are very, very rigid,” she continues. “That rigidity doesn’t work. We invite people to our table and their presence is always welcomed and honored, no matter what they offer. Yoga, reiki, art therapy…it all contributes to the big picture.”

Word of Tarpon Springs’ work has spread. Walla Walla, WA, used Peace4Tarpon’s memorandum of understanding as a model. And in Kansas City, MO, Trauma Matters KC has more than 100 people who have signed a similar memorandum. People in Traverse City, MI, Topeka, KA, Meadville, PA, Gainesville, FL, Warwick RI, and Missouri state government have sought advice from Saenger about how to start similar projects.

“This is a long-term initiative,” says Saenger. “There’s not an end date to this. When everybody’s participating, there will be a cumulative impact.”

____________________________

This is an update of an article about Tarpon Springs that I did in 2012, and is one of several articles about how different towns, cities, states and provinces are beginning to embrace an ACEs movement and become engaged in preventing/treating ACEs and promoting resilience. They were done as part of a Community Resilience Cookbook, produced by the Health Federation of Philadelphia with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Written By Jane Ellen Stevens

Tarpon Springs, FL, first trauma-informed city, embraces messy path toward peace was originally published @ ACEs Too High » Jane Ellen Stevens and has been syndicated with permission.

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts