Fact #1: People who were abused and neglected when they were kids have poorer physical and mental health. The more types of ACEs (adverse childhood experiences) – physical abuse, an alcoholic father, an abused mother, etc. – the higher the risk of heart disease, depression, diabetes, obesity, being violent or experiencing violence. Got an ACE score of 4 or more? Your risk of heart disease increases 200%. Your risk of suicide increases 1200%.

Fact #2: Mindfulness practices improve people’s physical and mental health.

Now, says Dr. Robert Whitaker, a pediatrician and professor of pediatrics and public health at Temple University, there’s one more important fact: People who are mindful are physically and mentally healthier, no matter what their ACE scores are.

This study, to be published in the October issue of Preventive Medicine, is the first to look at the relationship between ACEs, mindfulness and health. And it has implications for anyone, and especially those who take care of children– teachers, parents, coaches, healthcare and childcare workers.

Many people think of mindfulness as people sitting and saying “Ommmm.” There’s actually more to it, and it’s worth explaining. People who are not mindful don’t regulate their own emotions very well. Situations that trigger traumatic memories may cause a person to lose focus on what’s happening currently, and lead them to make snap judgments and have knee-jerk reactions of anger, frustration, or fear, which can further the spread stress and trauma. They may not even be conscious that they’re doing so. They also ruminate on situations they can’t control, and can’t let go.

Here’s what it’s like not to be mindful:

- “My co-worker’s angry today. I must have done something wrong. She’s JUST like my mother: moody, angry, a screamer. Well, I’d better get my defenses up and give her a piece of my mind before she attacks me.”

- “That kid keeps getting out of his seat and bothering the other kids. I know he’s making jokes about me and turning the other kids against me so that they won’t listen in class. He’s doing this on purpose just to aggravate me. That pisses me off and I just CAN’T HELP YELLING AT THE PUNK and I can’t WAIT to kick him out of class.”

- “That guy just cut me off!! Well, f**** him and the horse he rode in on!! I’ll show him. I’ll speed up, pass him and throw him the finger! That’ll teach him!”

Here are mindful reactions to the same situations:

- “My co-worker’s really upset today. She’s snapping at everyone, including me. I wonder what happened to her? I’ll see if we can find some quiet time and see if she wants to talk about it.”

- “Brian seems unsettled today. He’s jumping out of his seat and he’s over-reacting to his classmates. He was happy and engaged yesterday. I wonder if something happened at home or on the way to or from school? I’ll have a quiet word with him to see if he wants to talk about it and help him calm down.”

- “That guy just cut me off. He’s obviously in a hurry and isn’t paying attention. I wonder if he’s upset – that literally can cause tunnel vision. To avoid an accident, I’ll just hang back and not get in his way.”

“People who have somehow become more mindful are able to disconnect from things that bug them,” says Dr. Bruce McEwen, professor of neuroendocrinology at The Rockefeller University in New York, NY, and one of the study’s authors. And there’s some important physiology behind this response: If the daily fluctuation of the stress hormone cortisol goes from low to high and back again, he explains, a person tends to be healthier.

“They can turn it off and on when they need it,” he says. “If you can’t do that, if cortisol levels stay high or are inappropriately overactive, you’re in trouble. Persistently high cortisol levels and flat, unchanging cortisol over the day hurt our neurological systems.”

Those who are mindful are aware of the present situation, they can focus on what’s in front of them, and they observe while holding back on making judgments about other people or themselves. They react to other people’s rage, anxiety, indignation, annoyance, frustration and aggravation – whether intentionally aimed at them or not — by turning those chunks of stress flying around them into tiny droplets of water that roll off their duck-like backs.

Mindful coworkers create environments that are calmer. Mindful bosses stay grounded and optimistic no matter what happens. Mindful teachers create a safe place for their students and remain calm when helping even the most frazzled of kids. Mindful parents react with concern, interest, compassion and assistance when their children scream, rage, or cry in fear. The parents may feel anger, frustration or exasperation, but they can control those emotions.

Most important, Whitaker’s study shows that being mindful protects people from the physical and mental health effects of childhood trauma, which, according to the CDC’s Adverse Childhood Experiences Study, most people in the U.S. have experienced.

The study’s also important, according to Dr. Sandra Bloom, a psychiatrist and associate professor in the Drexel University School of Public Health and founder of the Sanctuary Model, because the results provide hope that people who have experienced abuse, neglect and other trauma in their childhoods and don’t have mindfulness can learn a technique that can be easily taught at low cost. “It’s a stress management tool that probably changes the physiology of arousal,” notes Bloom, who was not involved in the research.

“My perspective as a neuroscientist is on how brain function can be altered,” says McEwen. “That’s why I’m so excited about the research. Now I want to know if we can reactivate plasticity in someone who has had a significant number of ACEs, and increase compensatory mechanisms to live a better life and be more mindful.”

The details of the study are interesting because of its participants: 2,160 adults (98 percent of them are women) working in 66 Head Start programs in Pennsylvania. Over half are 40 years old or older; 86 percent are white; 61 percent finished college; 62 percent are married.

Head Start is the nation’s largest federally funded early childhood education program; nearly one million children are enrolled. The goal of Head Start is to prepare disadvantaged kids for school. More than 200,000 people – mostly women – work for Head Start. This includes teachers, managers, home-based visitors and family service workers.

“Increasing school readiness for children living in poverty is a tough mission and Head Start staff work for low wages in stressful jobs that have low prestige,” says Whitaker. “Yet, many people are asking why the program is not more effective. As a pediatrician, one of the first things I noticed when I spent time with Head Start teachers is that many of them looked really weary. When parents or teachers are worried, tired, stressed and preoccupied, they are not at their best and most of them know it. I felt it was important to understand how the teachers were doing. That included asking about childhood trauma, because we know it is common, can affect health and functioning, and can be reactivated in the workplace.”

Most of the kids who attend Head Start – including Early Head Start for children 36 months and younger – live in underserved neighborhoods and low-income families. Many have experienced – and continue to experience — complex trauma. Normal responses to complex trauma include erupting into anger, inability to focus or sit still, withdrawing, and distrust of adults. This adds an additional level of stress to Head Start staff, because they must keep their own emotions in check while they teach children how to recognize and regulate their feelings. And this is difficult if they have similar history that’s being triggered by the kids they work with.

Before this study, Whitaker had published information about the health of these 2,160 adults. It showed they had higher than expected rates of stress-related health conditions including obesity, asthma, high blood pressure, diabetes, headaches or migraines, low back pain and depression.

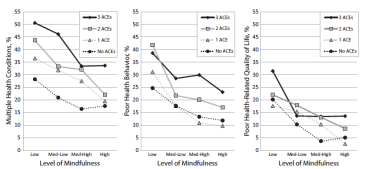

In the current study, Whitaker and his co-authors assessed eight ACEs (physical, sexual, emotional abuse; a family member who had problems with alcohol or drug abuse, who was depressed or mentally ill, or was in prison; witnessed a mother being abused and had parents who were separated or divorced) and mindfulness (using the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revise), and then looked at the prevalence of multiple health conditions, health behavior and health-related quality of life.

The mindfulness scale measures a person’s experience of her or his emotions or thoughts in four areas—focusing attention, being oriented to the present moment, being aware of an experience, and having an attitude of acceptance or non-judgment toward an experience. For example, two of the statements that people can agree or not agree with are: “I can accept things I cannot change”, and “I am able to pay attention to one thing for a long period of time.”

Of the 2,160 participants, almost 25 percent reported three or more ACEs, and almost 30 percent reported having three or more of seven stress-related health conditions — obesity, asthma, depression, diabetes, high blood pressure, headache, or back pain.

But among the participants with the highest level of mindfulness, the risk of having multiple health conditions was nearly 50% lower compared to those with the lowest levels, even for those who had many ACEs. Those who were more mindful reported more positive health behaviors – getting enough sleep, exercising more, and less smoking, binge drinking or binge eating – no matter how many ACEs they had.

The study’s results show that “it’s possible that mindfulness-based interventions may help people who have adverse childhood experiences have better health and functioning,” says Whitaker.

One of the questions that arises out of the study is how did the healthy people with high ACE scores become mindful? “I do not know,” says Whitaker. “I can only speculate.”

“What we know from other research is that the presence or connection with other adults who can help make sense and meaning of one’s life in the context of suffering helps a child become resilient,” he says, “a compassionate response from a person with whom the child feels safe.”

Even if there’s ongoing trauma in the household, says Whitaker, being heard, being seen, and being valued by an adult such as a caring teacher in a place that’s physically and emotionally safe, such as a trauma-informed school, will build resilience in a child and help that child grow up into a resilient adult.

A person’s genotype may also contribute, says McEwen. “A more reactive child may do very well in a supportive environment and worse than average in a dysfunctional environment.”

Whitaker and McEwen emphasize that this research is not just about Head Start and early education. “It’s important to consider the introduction of mindfulness and related practices for people,” especially for anyone who works with children, including parents, says McEwen, “not just for Head Start workers.”

Many of the Head Start workers who participated have found the research “very informative and helpful,” says Paula Margraf, program director of Community Services for Children, a large Head Start/Early Head Start program in Allentown, PA.

“It gave us great insight into the thinking, beliefs and attitudes of our staff,” she notes. “It helped us to understand how stressful their jobs are, and how this will impact on their interactions with children and parents.”

Mindfulness is now at the top of the agency’s agenda. The staff launched a wellness committee that promotes information and training about healthy behaviors, and for the last two years, a Pennsylvania State University professor has trained all staff members in mindfulness.

Written By Jane Ellen Stevens

Mindfulness protects adults from physical, mental health consequences of childhood abuse, neglect was originally published @ ACEs Too High » Jane Ellen Stevens and has been syndicated with permission.

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts