________________________________

For millions of troubled children across the country, schools have been toxic places. That’s not just  because many schools don’t control bullying by students or teachers, but because they enforce arbitrary and discriminatory zero tolerance school discipline policies, such as suspensions for “willful defiance”. Many also ignore the kids who sit in the back of the room and don’t engage – the ones called “lazy” or “unmotivated” – and who are likely to drop out of school.

because many schools don’t control bullying by students or teachers, but because they enforce arbitrary and discriminatory zero tolerance school discipline policies, such as suspensions for “willful defiance”. Many also ignore the kids who sit in the back of the room and don’t engage – the ones called “lazy” or “unmotivated” – and who are likely to drop out of school.

In the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), which banned suspensions for willful defiance last May, the CBITS program (pronounced SEE-bits), aims to find and help troubled students before their reactions to their own trauma trigger a punitive response from their school environment, including a teacher or principal.

Gabriella Garcia’s son attended Harmony Elementary School during the 2012-2013 school year. The school has 730 children in kindergarten through fifth grade. She says without CBITS, she would have lost custody of him and her other two children. “But for some reason,” she says, “I let him (her son) take that test.”

“That test” is a questionnaire given to some of the fifth-grade students at the school, which is located in a mostly Hispanic neighborhood south of downtown Los Angeles.

Every semester, Lauren Maher, a psychiatric social worker, gives all the children in Harmony’s fifth grade a brightly colored flyer to take home. It asks the parent to give permission for her or his child to fill out a questionnaire about events the child may have experienced in, or away from, school. “Has anyone close to you died?” “Have you yourself been slapped, punched, or hit by someone?” “Have you had trouble concentrating (for example, losing track of a story on television, forgetting what you read, not paying attention in class)?” are three of the 45 questions.

Garcia’s son was one of a small group of students whose answers on the questionnaire, as well as his grades and behavior, were showing signs that he was suffering trauma. He joined one of the two groups, each with eight students that met once a week for 10 weeks at the school. In the group, the students don’t

talk about the event or events that triggered the trauma. Instead they talk about their common reactions to trauma, and learn strategies to calm their minds and bodies.

Each student also meets twice individually with Maher; so do the child’s parent or parents. For some parents, it’s the first time they hear about the traumatic event – such as bullying or witnessing violence in the neighborhood – or what their child says about a traumatic event. So, if a child throws a fit because he doesn’t want to go to the grocery store, says Maher, it’s not because he’s being a bad kid. It’s because he remembers how during his last trip to the grocery store, his mother threw her body over his when gunfire broke out and wouldn’t let him move until the police came to help them, and now he’s afraid to return.

In the case of Garcia’s son, he was having problems at school because he was witnessing his stepfather beating her up. The first time Garcia talked with Maher, Garcia wondered what she had gotten herself into. “I didn’t know if she would call the department of social services on me or not,” she says, tears streaming down her face.

“After I had a talk with her, I realized it wasn’t a bad choice,” she says. “At first, it hurts to open up, because you don’t want anybody to know about your situation. I was a victim of domestic violence and never opened my mouth. We’re taught that what happens at home stays at home. I was reassured that I wasn’t the only one going through this.”

Lauren Maher, psychiatric social worker at Harmony Elementary School in Los Angeles, CA.

_____________________________

Maher gave Garcia contacts at the Children’s Institute, which arranged for counseling for her and her sons. Garcia soon asked her husband to leave. In the meantime, her sons’ biological father wanted custody of their sons, but because she was able to provide proof from Maher and the therapists that she and her children were receiving help, were on the mend, and that the abuser was no longer in their lives, her children were able to stay with her.

Responding to student trauma

CBITS had its beginnings in 1999, when clinician-researchers from RAND Corporation and the University of California at Los Angeles teamed up with LAUSD School Mental Health to develop a tool to systematically screen for their exposure to traumatic events. The screening tool – a questionnaire – was first used with immigrant students, says Escudero. When it became evident that students were witnessing violence in their neighborhoods and domestic violence and other abuse in their homes, social workers began making it available for all students. This experience led the team to develop CBITS. Since 2003, CBITS has been disseminated through the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, and is used in hundreds of schools in the U.S. and other countries. It has a new site – traumaawareschools.org – that is focused on helping schools implement CBITS and teacher training.

“I was one of the originators of CBITS,” says Pia Escudero, director of the LAUSD School Mental Health, Crisis Counseling & Intervention Services. “When we started, folks did not want to talk about family violence. Our gateway was to talk about community violence.”

With the screening tool, it really didn’t matter what the specifics were – CBITS was able to identify children who were having symptoms and needed help. Without it, says Escudero, “you only notice the kids who are acting out. You don’t get the kids who are introverted or depressed. But they’re full of anxiety and can’t function.” The screening tool also helps social workers identify children and families who need assistance the school cannot offer, as in Gabriella Garcia’s case, and provides resources for them.

Helping students’ social and emotional development

Like all schools in LAUSD, Harmony Elementary has taken several steps toward addressing social-emotional side of children’s development. It integrated PBIS (Positive Behavioral Integration and Support) that sets basic expectations for kids’ behavior in all school settings, and Second Step, which teaches kids empathy and emotional management as a way to prevent violence. Maher began a Peacemakers group, in which students are trained to help prevent and diffuse arguments between their peers. The school developed a support team – comprising principal or assistant principal, social worker, teachers, coaches, and administrators – that meets regularly to help the 25 percent at the school who are flagged for behavior, attendance or academic concerns.

_______________________________

But until it began using CBITS, the school wasn’t catching the children who were on the way to developing severe symptoms — either acting out or withdrawing – that would risk them falling into the suspension-and-expulsion/drop-out abyss.

And there are many of those children who attend Harmony. They come from families that live just above, at, or below poverty level. Many are immigrants, and have suffered trauma in their countries of origin, in their journey to the U.S., and in adjusting to a new culture and language. The school’s 30% annual turnover rate of students speaks to the disrupted lives of people in the community.

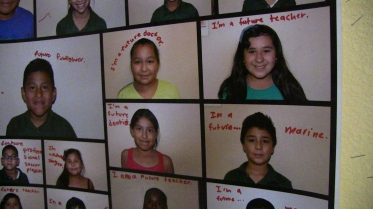

The doorway to classroom of fifth-grade teacher Veronica Marquez, a 2012 California Teacher of the Year.

_____________________________

Before she became principal in 2011, Sylvia Salazar, a 30-year veteran of LAUSD, had never heard of CBITS. “I never worked at a school where mental health services were provided,” she says. “Now I don’t understand why all schools don’t have this.”

LAUSD’s discombobulated approach to children’s social-emotional development

But Harmony is also an example of the miles and miles and miles that it and other schools in LAUSD still have to travel before making good on LAUSD Superintendent John Deasy’s promise to educate all students. “All,” he notes on the LAUSD web site home page. “Not some, but all.”

Severely limited resources, no targeted trauma-informed training for teachers, including a lack of ensuring that all educators learn about the science of adverse childhood experiences, and a disorganized approach to implementing education, programs and practices about social-emotional learning result in a hit-or-miss approach, with the outcome that students and teachers both suffer.

Limited resources. As well as CBITS works for the students who participate, Maher says she doesn’t have enough resources to work with all the students who could use the help, even though she has eight to 10 interns who provide an additional 14 to 16 hours of assistance each week.

“In an ideal perfect world where I had more time, I would screen every child,” she says. And she believes that half of the students could use assistance. As it stands, once she receives permission from parents, she checks academic and behavioral records to identify those who very clearly need help before she has them fill out the CBITS questionnaire, because she doesn’t have enough resources to help them all. In addition, CBITS isn’t offered to children in grades K-4, when it’s clear that many of them could use assistance.

Maher would also expand the parents groups. During the last school year, she organized two groups for parents so that they could also talk about their own trauma, and give them help in learning how to calm themselves. Most of them have experienced childhood trauma. Without intervention, many parents tend to pass on their own trauma to their children.

No trauma-informed training for teachers. Although CBITS offers a training program (SSET – Support for Students Exposed to Trauma) for teachers, LAUSD hasn’t implemented it. And since the teachers aren’t trained, those who don’t understand how their actions can inadvertently traumatize their students continue to trigger students.

____________________________

I saw this happen during a rehearsal for a school performance at Harmony Elementary last May. Two teachers were choreographing a dance routine with students from the fifth-grade classes. One teacher led her group of students with laughter and encouragement, and the smile never left her face. She obviously enjoyed what she was doing, and her students did, too, as they learned the steps. The other teacher, a dark frown creasing her face, barked orders and stomped around while wielding a large umbrella. Her students whispered fearfully, were uncertain in their movements, and afraid of being snapped at. By the end of the rehearsal, several had disengaged to sit on the sidelines, their heads hanging in misery or anger.

On either side of Lauren Maher (on left) and Pia Escudero, students sit out dance rehearsal after becoming disheartened.

_______________________________

Many educators still think students’ “bad” behavior is deliberate, and that the kids can control it. But it’s often not, and they can’t – not without help, says Dr. Joyce Dorado, director of HEARTS — Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools, and associate clinical professor in the University of California San Francisco Department of Psychiatry, Child and Adolescent Services. Their behavior is a normal response to stresses they’re not equipped to deal with, she explains.

Almost half the nation’s children under the age of 18 have experienced at least one or more types of serious childhood traumas, as measured by a recent survey on adverse childhood experiences by the National Survey of Children’s Health (NHCS). This translates into an estimated 35 million children nation-wide.

Since parents responded to the survey, questions about physical, sexual and verbal abuse were excluded, because it was unlikely those would be answered accurately. Hence, 35 million children suffering childhood trauma is on the low side.

A more accurate picture comes from CDC’s Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study), which shows that serious, chronic childhood trauma is so common that two-thirds of U.S. adults have reported experiencing at least one type out of ten measured by the study. These adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) include physical, sexual or verbal abuse; physical or emotional neglect; and five types of family dysfunction — family violence, living with alcoholic (or other drug-addicted) or mentally ill parents, losing a parent to divorce or abandonment, or a family member who’s in prison.

Dorado says it’s important for teachers to become “trauma-informed” – that is, to learn about the effects of ACEs and to receive training in how to work with children who’ve experienced or are experiencing trauma. That’s because the toxic stress caused by trauma can harm children’s brains, she explains, making kids susceptible to being triggered into “fight, flight or freeze” mode, even when they aren’t actually being threatened. As a result, they can have trouble concentrating, learning, or sitting still. At the slightest trigger – a teacher yelling at them or another student accidentally knocking into them — they can erupt into rages, lash out at others or hurt themselves. Or they can withdraw in fear and not participate in anything that’s going on around them. None of this behavior is intentional, says Dorado.

Trauma-informed practices are not meant to replace other frameworks such as PBIS, Safe & Civil Schools, or restorative justice, says Dr. Christopher Blodgett, director of the Washington State University Area Health Education Center, whose research shows a direct link between ACEs and academic failure. Becoming trauma-informed not only supports those approaches, it’s the bedrock for all of them, he says. And, in fact, schools in Spokane, WA, and Brockton, MA, that use PBIS have integrated trauma-informed practices.

Disorganized approach to improving social-emotional learning and school climate. LAUSD is a huge school system – the second-largest in the nation. More than 650,000 students attend more than 900 schools and more than 180 public charter schools, each of which operates with a great deal of autonomy when it comes to implementing programs and practices to improve the social and emotional development of children.

PBIS, which is required in all schools, is implemented unevenly. Community schools programs, which involve matching students’ needs with community resources — come out of one department, restorative practices another.

Escudero’s School Mental Health department provides 300 psychiatric social workers in mental health clinics, wellness centers, special education programs, and in about 50 schools. That leaves more than 1,000 schools without any social workers, leaving hundreds of thousands of students without access to proper care.

Social worker Lauren Maher (l) and School Mental Health Director Pia Escudero at Harmony Elementary School in Los Angeles, CA.

____________________________

Without a collaborative effort to ensure students who need a higher level of care get that care, says Escudro, students can be exposed to trauma triggers, which can make their symptoms worse, and impede their ability to learn and progress in school.

According to Helping Traumatized Children Learn, a two-volume series developed by the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative in Boston, MA, a comprehensive school-wide system includes a basic understanding of children’s physiological and behavioral response to trauma, and the tools, programs and policies that prevent more trauma in their lives, including helping other students, teachers, families and the school system to stop traumatizing already traumatized children, and to incorporate resilience-building practices into individuals, families, the school system and communities. This includes teaching children how to calm themselves and to work with others (social-emotional program such as Second Step), restorative justice, secondary trauma awareness and tools for teachers, community school development, a school-wide system of behavior expectations, and changing school and district policies to respond to student behavior with support and compassion instead of punishment.

Despite all of the challenges that LAUSD faces, Escudero is optimistic. The district just opened 13 wellness centers, and Escudero expects more to open. They are being funded from money that is normally designated for soccer fields and pools. “With these wellness centers, we can identify and serve children with the highest rates of medical needs, the highest rates of trauma, pregnancies, and health factors that impede academic achievements,” she says. “We hope to integrate trauma exposure into clinical practice.”

Escudero believes that the commitment to the wellness centers, the waiver LAUSD received from penalties under the No Child Left Behind law and California’s Local Control Funding Formula have opened a door to put more resources toward children’s social and emotional growth, as well as providing children with physical, mental and dental health services. This has the potential to nearly eliminate suspensions and expulsions by creating safe school environments and helping traumatized children so that they’re able to succeed and learn.

“Up to now, it’s been a very academic-measurement world,” she says. “But we’ve been having a lot of conversations with the administrators, school sites and human resource department on how to train teachers and support them with trauma informed and self-care techniques. This will also help with retention. A lot of teachers leave because they’re taught to teach, but they’re not equipped to handle all the other stresses students bring into classroom.”

“If I ruled the world,” she continues, “I would make all schools in the district trauma-informed and provide trauma-specific services to detect and treat trauma early. It takes time and commitment. Changing the school culture, that’s hard.”

______________________________

This is part of an investigative series into “right doing” – how some schools, mostly in California, are moving from a punitive to a trauma-informed approach to school discipline. The series includes profiles of schools in Le Grand, Fresno, Concord, Reedley, San Francisco, Vallejo, and San Diego, CA; and Spokane, WA, and Brockton, MA. The series is funded by the California Endowment. ![]()

Written By Jane Ellen Stevens

Trying to make LA schools less toxic is hit-and-miss; relatively few students receive care they need was originally published @ ACEs Too High » Jane Ellen Stevens and has been syndicated with permission.

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts

Great story! Wow!