__________________

Suzanne Savall, principal of Otis Orchards Elementary School in Spokane’s East Valley School District, says she didn’t really know what she was signing up for, but the words “complex trauma” resonated with her in 2008, when she heard about a workshop that was being offered by the Washington State Area Health Education Center (AHEC).

From the moment 54 teachers and support staff, including custodians and cooks, finished the six-hour workshop in 2008, they never looked back. After five years — the last two during which Natalie Turner, AHEC assistant director, and AHEC project associate Bonnie Wagner did monthly training workshops with the school’s teachers and staff, and weekly on-site consulting — Otis Orchards can call itself a trauma-informed school. What’s the difference between then and now?

Here’s a conversation that Suzanne Savall and I had about how Otis Orchards changed to a trauma-informed school, and what the effects have been.

Q: How did you hear about this training?

Savall: I knew that another school had been trained in complex trauma. Those words resonated with me. I believe it was because I had ACEs in  my childhood. I was a brand new principal. After teaching here for 25 years, I knew that lots of our kids had complex trauma. When the assistant superintendent asked if I could get 95% of the staff to volunteer their time for six hours, I said: “I can do it.” And we did it. We had everybody but one staff member.

my childhood. I was a brand new principal. After teaching here for 25 years, I knew that lots of our kids had complex trauma. When the assistant superintendent asked if I could get 95% of the staff to volunteer their time for six hours, I said: “I can do it.” And we did it. We had everybody but one staff member.

Q: How did you get the staff interested?

Savall: I told them it was an opportunity. I told the staff that they would get something special and our kids would get something special. I told them that we’re starting on a journey and there’s no turning back. “If you’re interested in looking at things through a trauma lens, stay here,” I said. “If you’re thumbs down, maybe you’d better move on.”

Q: What was the most useful thing you learned at the workshop?

Savall: The brain research was profound to me – how toxic stress changes the development of a child’s brain. And how kids can go through terrible things and have resilience through it all if they have a caring adult and caring environment. It gave me hope that we can save these kids.

Suzanne Savall, principal of Otis Orchards Elementary School, greets Natalie Turner, assistant director of the Washington State University Area Health Education Center

_______________________

The staff reacted the same way. There was some concern, because teachers’ plates are so full. We said, “We’re not adding to your duties. This is going to help your days go smoother.”

Research had shown that this could make a lot of difference in students being able to succeed in school. We were told that it was going to impact our students’ schools. Lo and behold, for the next three years we’re a school of distinction. (This award is given when a school is in the top 5% of schools that improve academically over five years.)

Q: What happened after that first workshop in 2008?

Savall: We asked for more. We got a couple more short trainings, but it wasn’t enough. The carrot was: By engaging with them (AHEC) early, we might be able to dig in when they had funding. That came as a result of the incidence and prevalence study [that showed how many Spokane children had ACEs.] When I told staff about that research, they said that we really have to do something now. We just can’t let it go. The teachers wanted tools.

Q: What did the school do as a result of the training?

Savall: We created the complex trauma committee in 2010 — five teachers and five classified workers (cook, playground supervisor, secretary). That committee generated so many changes. One was OTIS time — Opportunity To Interact with Students. When students come to school upset in the morning, they need that chance to be able to get that off their chest. The committee said, what if we take those first 15 minutes of school for OTIS time? That gives students a chance to talk with their peers, to talk with teachers, to move the classroom from being chaotic to being calm and organized. The kids know that they’re going to be greeted at the front door, and at the classroom door, where they have one more opportunity to get their feelings out.

Q: Do you have an example of how this works?

Savall: Just yesterday, a second-grader came to school and I could see right away that he was upset. His dad had hit his mother, the cops came and dad was taken off to jail. I asked if he wanted to talk. He wanted to have breakfast, so he did that. At end of OTIS time, I play music for 90 seconds over the loudspeaker, so that it’s not an abrupt change. He came in after that, too upset to talk. I have a bunch of different ways that children can soothe themselves in here. He put on earphones to block out everything, and wrapped himself in the weighted blanket. I told him to keep an eye on the clock, and after five minutes, tell me how he was doing. After five minutes, he said, “I want to talk.” He blurted out a lot of different things, mostly that he was scared for his mom. So, we got mom on the phone, he was able to talk to her, tell her how concerned he was. She told him that things were going to be fine, and calmed him down. After the phone call, he asked if he could make a design in the small rock garden I keep on my desk. Drawing in the sand is another way for students to soothe themselves. Then he went back to class. I checked in on him at 2 p.m. He gave me a thumbs-up. He didn’t have another meltdown.

Savall: Just yesterday, a second-grader came to school and I could see right away that he was upset. His dad had hit his mother, the cops came and dad was taken off to jail. I asked if he wanted to talk. He wanted to have breakfast, so he did that. At end of OTIS time, I play music for 90 seconds over the loudspeaker, so that it’s not an abrupt change. He came in after that, too upset to talk. I have a bunch of different ways that children can soothe themselves in here. He put on earphones to block out everything, and wrapped himself in the weighted blanket. I told him to keep an eye on the clock, and after five minutes, tell me how he was doing. After five minutes, he said, “I want to talk.” He blurted out a lot of different things, mostly that he was scared for his mom. So, we got mom on the phone, he was able to talk to her, tell her how concerned he was. She told him that things were going to be fine, and calmed him down. After the phone call, he asked if he could make a design in the small rock garden I keep on my desk. Drawing in the sand is another way for students to soothe themselves. Then he went back to class. I checked in on him at 2 p.m. He gave me a thumbs-up. He didn’t have another meltdown.

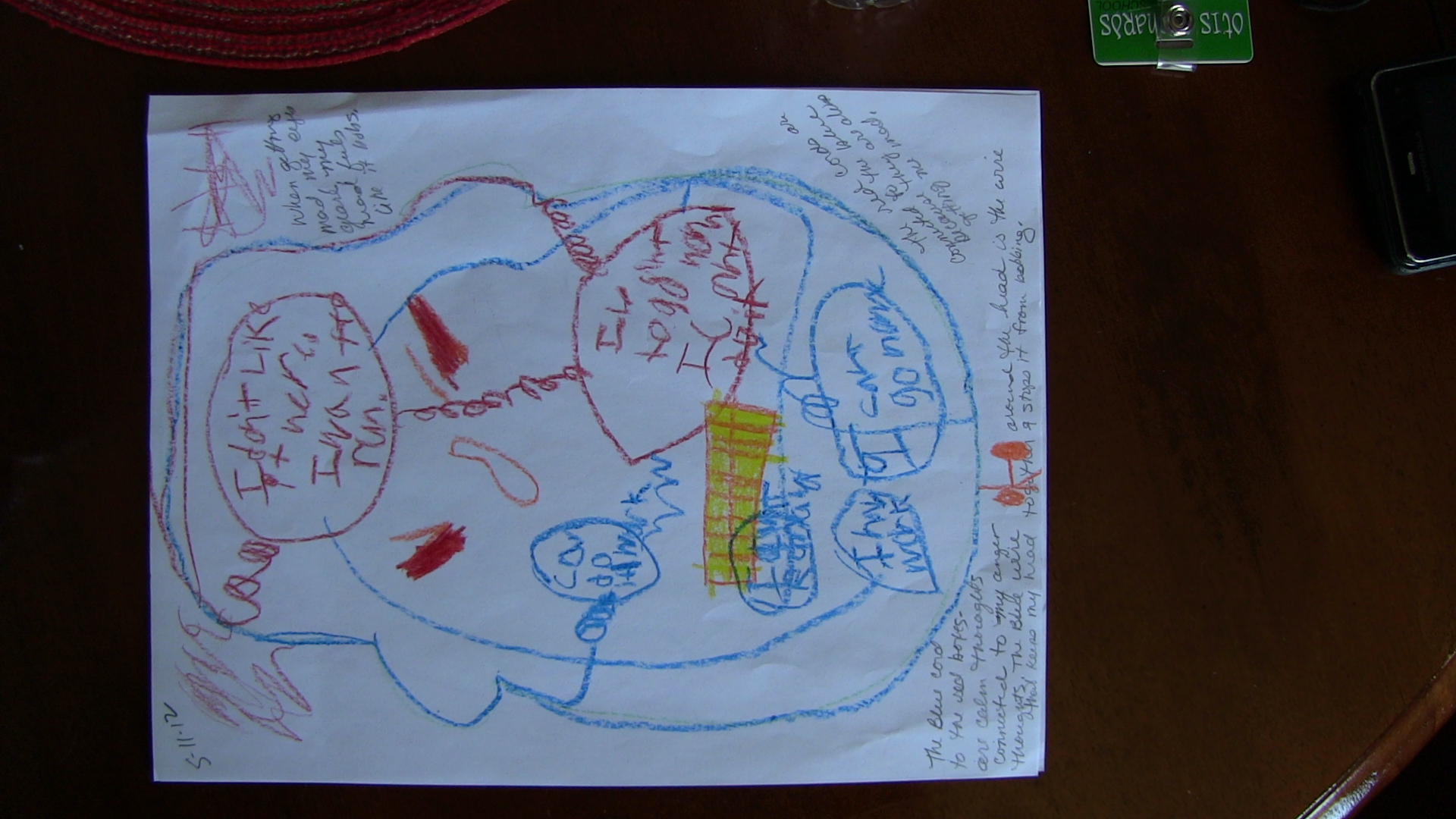

This happens at least once a day with a student. But if they come in here and spend time soothing themselves, I never see them again the rest of the day. I have a weighted blanket that a physical therapist gave me. I would recommend it for everybody. When kids are unable to use their words, another strategy is that I invite them to draw picture of what is in their head. I ask them, if I were looking down into your brain, what would I see? It’s a way to express themselves, to get their feelings out.

Another strategy the committee developed to help kids be calm was to have every classroom post a daily schedule. Some teachers put a copy on the desk of students who have the most uncertain lives. The committee also changed student notifications. Kids with trauma always worry about who’s going to be home. We used to announce kids’ names on the loudspeaker, with the changes in who was to pick them up or at what time. That meant lots of startling interruptions in the afternoon. Now, the 7th graders take messages to classrooms and lay them on teacher’s desk. That’s helped calm things down.

Q: You say that you give your teachers permission to try different things. Is there something that you’ve done differently that modeled this for your teachers?

Savall: I changed how we deal with aggressive behavior on the playground. If a child has pushed another, a playground teacher will write up a white slip. The punishment used to be automatic – they had to spend time standing against the wall, and they couldn’t participate in recess.

Now, I decide whether they get time on the wall. I want the intervention to be a learning opportunity for the child. They bring the white slip and talk with me about what they did. Then I tell them: I’ll make a deal. This is the first time you’ve ever done this. If you don’t believe you can stop yourself next time a similar situation occurs, then you’ll do one day on the wall and I call your parents. If you say, “I promise I won’t do it again,” if you think you’ve truly learned your lesson, I won’t call your parents. I’ll put this white slip in your file. But if you push someone again, you’ll get five days on the wall and I call your parents.

I’ve had only one student blow it so far, out of 25.

Q: Did you apply to be one of the six pilot schools to become trauma-informed?

Savall: I was asked if we wanted to be a part of that grant. When we found out that we had it, we had a celebration at Otis.

We’ve been doing professional development around the ARC model. What it’s transformed into is that we are doing case studies, and applying that knowledge. We create a case study of student at Otis, and come up with plans. Different staff will step up and say, I can offer something. For a student who needs more interaction with caring adults in his life, a 5th grade teacher might offer to have lunch with him on Fridays. Another teacher will offer to draw with the student during lunch. Different staff will jump in who never would know that student otherwise.

Q: Natalie Turner (AHEC’s assistant director and the main trainer) says that it was important for the staff to shift from spending 90% of their time on the 10% most difficult kids, to spending 90% of their time on 90% of the kids, including the kids that internalize their trauma instead of acting it out. Has that made a difference?

Savall: Yes. If you set that base, there’s not going to be as many triggers for any children. We come up with a loose plan, then tighten it up as we get experience. With all the students, it’s had a positive impact.

Q: What else are you planning?

Savall: The staff wants to take time at the beginning of the year, so that the previous year’s teacher can talk about that kid with that kid’s teacher for the year. They want to be able to say: “This is a child of trauma. These are the strategies that worked,” so that new teachers don’t have start all over again.

Q: What’s been the effect of the changes you’ve made?

Savall: Otis is known around the region as a school that really cares about its students. We continue to have students from inside and outside the district choose to go here because of that reason. The ‘lens’ that we use when looking at our students and their families is totally different. We know now that they are doing their best. Students do not come to school to make their teachers frustrated; they come to be a part of a school that will keep them safe and hold high expectations. It is up to us to help them keep themselves regulated.

Our incidents of aggressive behavior — pushing, hitting, physical aggression — dropped from 83 to 13 during this January to April, compared with the same time last year. Earning the School of Distinction Award for being in the top 5% of state in improvement of overall reading and math test scores has been awesome for staff students and parents to get recognition. Not only are our kids happier, but our staff is very supportive of each other, and proud to be a part of this work.

![]()

By Jane Stevens

Aces Too High

The story Q-and-A with Suzanne Savall, principal of trauma-informed elementary school in Spokane, WA was originally published @ Aces Too High and has been syndicated with permission of the author.

Sources:

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts