As you may recall, the first blog in this series, Reason #1 for the Heroin Epidemic was “Blame the Doctors”. And now here we are again implicating the medical profession as a contributing factor. But this week I want to focus on the medical education process. To state it bluntly, Addiction Medicine training and emphasis on the complexity and interrelationship of addiction and underlying associated illnesses is lacking in our medical schools and residency programs. This not only leads to a lack of appreciation of the importance of screening patients for predisposition to and/or ongoing addiction, but also creates biases. In general, misconstruing of complex societal issues can lead to preconceptions that are not based in fact. When this hypothesis is applied to physicians who are asked to treat the difficult and the multifactorial aspects of addictive disease, bias can prevail. There are certain diseases that are more time consuming to manage than others, especially when the patient is either in denial and/or non-compliant. Examples may include Diabetes, Cardiac Disease and Lung Disease. But physicians in general receive the appropriate training to deal with the demands of these patients. That is not the case with addictive illnesses and bias is compounded by the other societal factors that influence perceptions, such as jailing patients (please see excerpt below).

However, inroads are being made to correct this deficiency. COPE (Coalition on Physician Education in Substance Use Disorders) is one such organization that is making great inroads within the medical educational process, and I felt honored to be chosen as a speaker at a recent event. I presented some facts such as:

- The changing face of addiction now includes aging baby boomers and heroin addiction is no longer just an inner city problem, as it has migrated to college campuses and to white suburban men and women in their late 20’s;

- Physicians can make a tremendous difference by implementing a brief discussion or form with their patients to rapidly identify patients at risk. The tool is called SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral for Treatment); and most importantly

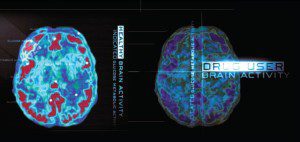

- “Drug addiction is a brain disease that can be treated” (Nora D. Volkow, M.D., Director, National Institute on Drug Abuse)

Physician bias is another roadblock to solving the heroin epidemic, because biased doctors are less likely to treat patients with addiction, and as discussed in last week’s blog, it is essential to attack this scourge to society by decreasing demand through treatment and education. We need more doctors willing to treat patients and also to be more involved in educating our citizens and public officials that treatment works. Our medical schools and residency programs need to do more.

I am pleased that I have been asked by a medical school to use my book as a teaching tool to destigmatize the disease of addiction. And yes, it is time to stop jailing patients, as best discussed by Saul Tolson in the following excerpt from Addiction On Trial.

Pausing while attempting to make eye contact with each and every individual in the audience before proceeding, Dr. Tolson delivered his next few lines in a compassionate tone. “With no disrespect, but as a way to reinforce the point I am trying to make, I’d like to ask you to please tell me the difference between a nicotine or alcohol addict, who in some cases may even receive a heart or liver transplant, and someone addicted to heroin or cocaine? Why are those afflicted with the disease of addiction to certain drugs treated so differently than patients who suffer from nicotine or alcohol addiction or other chronic diseases like diabetes? Are they really any different?”

Dr. Tolson never relinquished the podium without one last attempt to convert the naysayers. “Now for those of you who fail to agree with me, and I know you’re out there, let me appeal to your wallets. To incarcerate one addicted patient—that’s right, jailing patients—costs between $40,000 and $50,000 per year. A one-year stay for a patient in a halfway house costs society about $20,000 per year and this does not include any medical care. But to treat one heroin addict as an outpatient with regular individual and/or group counseling sessions, ongoing urine drug testing to monitor for illicit drug use, a complete admission physical exam including laboratory tests that screen for contagious diseases such as Hepatitis C and HIV, and the daily monitoring of medication administration costs approximately $5,000 per year! That’s right—only $5,000 per year or about one-tenth the cost of putting this patient in jail!

Like they say in the Midas commercial, ‘you can pay now or you can pay later, but you’re gonna pay.’ Thank you all for your attention. I am able to stay for questions.”

Uncomfortable with the inevitable applause, Dr. Tolson kept repeating through the clapping, “So, there must be some questions.” The questions came, but none of his answers carried the consequences of those he would have to give to questions posed while under oath at the murder trial of James Frederick Sedgwick in Downeast Maine.

Written By Steven Kassels

Heroin Epidemic: Reason #8 – Physician Training & Biases was originally published @ Addiction on Trial and has been syndicated with permission.

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts