Nearly two-thirds of California adults have experienced at least one type of major childhood trauma, such as physical, verbal or sexual abuse, or living with a family member who abuses alcohol or is depressed, according to a report released last week.

The report – “Hidden Crisis: Findings on Adverse Childhood Experiences in California” (HiddenCrisis_Report_1014) – also reveals the effects of those early adversities: a startling and large increased risk of the adult onset of chronic disease, such as heart disease and cancer, mental illness and violence or being a victim of violence.

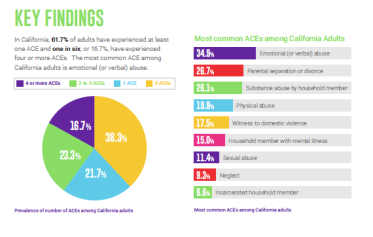

Ten types of childhood trauma were measured. They include physical, sexual and verbal abuse, and physical and emotional neglect. Five family dysfunctions were also measured: a family member diagnosed with mental illness, addicted to alcohol or other drug, or who has been incarcerated; witnessing a mother being abused, and losing a parent to separation, divorce or other reason.

Each type of trauma counts as an ACE (adverse childhood experience) score of one. The more ACEs a person has, the higher the risk of facing physical, mental and social problems.

For example, Californians who have an ACE score of 4 or more are nearly twice as likely to have asthma, 2.4 times as likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 1.7 times as likely to have kidney disease, and 1.5 times as likely to have a stroke. They’re five times more likely to be depressed and four times more likely to develop dementia or Alzheimer’s. Those with an ACE score of 4 or more are approximately three times more likely to smoke, binge drink and engage in risky sexual behavior. They’re nearly 12 times more likely to be the victim of sexual violence after they’re 18 years old.

One in six Californians – 16.7% — has an ACE score of 4 or higher. (Got Your ACE Score?)

The report clearly shows that “California is facing a major public health crisis that until now has gone largely unaddressed,” says Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, a pediatrician who is the founder and CEO of the Center for Youth Wellness in San Francisco, CA, which commissioned the Public Health Institute in Oakland, CA, to do the report.

PHI research program director Marta Induni analyzed data from four years of statewide telephone surveys of more than 27,000 adults. The data was gathered by the California Department of Public Health for the state’s Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System, which tracks hundreds of physical and mental health trends in the state. DPH has done its own in-depth analysis of the data, but has not yet released a report.

The survey has its origins in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-Kaiser Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study), first published in 1998. Dr. Vincent Felitti and Robert Anda developed the 10-question ACE survey, and measured those 10 types of childhood trauma in 17,421 members of Kaiser Permanente in San Diego. They were mostly white, middle- and upper-middle class, college-educated and all had jobs and great health care.

The ACE Study revealed four important findings:

– Childhood adversity is very common – 66 percent experienced at least one type of childhood trauma.

– If there’s one type of childhood trauma, there’s an 87% chance that there are others. In other words, traumas such as child sex abuse rarely happen alone.

– The more types of adverse childhood experiences, the higher the likelihood of long-term effects.

– ACEs are responsible for a big chunk of workplace absenteeism, and costs in health care, emergency response, mental health and criminal justice. So, the fourth finding from the ACE Study is that childhood adversity contributes to most of our major chronic health, mental health, economic health and social health issues.

Burke Harris hopes the California report will motivate policymakers to look at how ACEs are affecting health care costs in California and the nation. “Right now, the U.S. spends 18% of its GDP on health care, 75% of that on chronic diseases,” she says. “Nobody’s looked at the link to childhood adversity. I’m willing to bet my medical license that if we understood that link and did something about it that we’d not only saves lives but save money.”

She also believes every medical school should teach students about ACEs research, and all physicians should screen their patients for their ACEs.

Burke Harris handed out the report November 5th-7th to more than 200 people from the public health, medical, education, juvenile justice and child welfare communities who attended the state’s first ACEs summit in San Francsico.

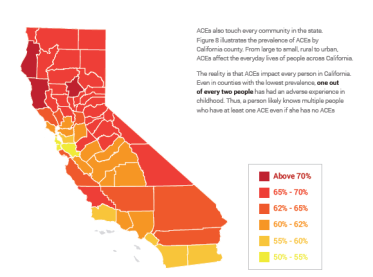

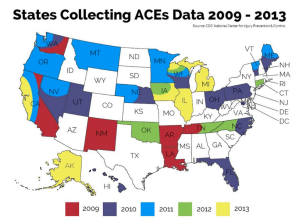

California is following the lead of many other states – including Washington, Iowa, and Maine – that have also held ACEs summits. And although the report’s results are similar to 25 other states and the District of Columbia, which have also done ACE surveys, there were a couple of findings that surprised Burke Harris.

California is following the lead of many other states – including Washington, Iowa, and Maine – that have also held ACEs summits. And although the report’s results are similar to 25 other states and the District of Columbia, which have also done ACE surveys, there were a couple of findings that surprised Burke Harris.

“It was a surprise to me how consistent the findings were across ethnicities,” she says. “In Caucasians, 16.4% had an ACE score of 4 or more; in African Americans the percentage was 16.5%. It was a little higher in Hispanics, and lower in Asian and Pacific Islanders.”

The variations come in looking at across economic strata — poor people tend to have higher ACE scores than wealthier people – and in health access. People with high ACE scores have much less access to physicians and health services than people with low ACE scores.

She was also surprised to find that the counties with the highest ACE scores were rural, specifically Humboldt County, with 30.8% of its residents having an ACE score of 4 or higher, and Butte County not far behind.

Even though people with high ACE scores tend to cope in ways that harm their health – such as smoking, binge drinking, overeating, or engaging in thrill sports – emerging research shows that high-risk behavior accounts for only 50 percent of the increased health risk, notes Burke Harris.

The explanation for ACES lies in the toxic stress caused by childhood trauma. Unlike positive stress, which we all need to develop into healthy adults, toxic stress causes the body to stay in a red alert mode – always ready to fight, flee or freeze — which puts a lot of wear and tear on the body’s systems. Toxic stress can change the structure and function of a child’s developing brain, damage the immune system, hormonal system, and even change the way our DNA is read and transcribed, says Burke Harris.

The ACE Study and the subsequent state ACE surveys all ask adults about their childhood experiences that occurred sometimes decades ago. It’s a little more difficult to get at current ACE scores of children, because it’s unlikely that parents would admit to a crime: abusing their children. However, National Survey of Children’s Health can get close by measuring several ACEs. Their figures for California are also grim — even without physical, sexual and verbal abuse or physical and emotional neglect, nearly 20 percent of California children under the age of 18 have two or more ACEs.

The neurobiology, biomedical and epigenetic consequences of the toxic stress caused by childhood trauma is part of an emerging unified science of human development that includes resilience research and trauma-informed practices.

Many organizations – including schools, hospitals, homeless shelters, public health clinics, pediatric clinics, courts, police departments and even cities and counties – are implementing trauma-informed and resilience-building practices based on ACEs research.

- Pediatricians and public health clinics are screening patients for ACEs. Jeffrey Brenner, MacArthur genius award winner, recommends physicians adding ACE screening to measurement of other vital signs, such as blood pressure.

- Many schools – including schools in San Francisco, CA, Spokane, WA, and Walla Walla, WA— have integrated trauma-informed practices into classrooms, playgrounds and school policies.

- Head Start (early childhood education program) in Kansas City has integrated trauma-informed practices in a program called Head Start Trauma Smart. (NYTimes article about the program.)

- Home-based early childhood intervention, such as Child First. (NYTimes article about the program.)

- Police departmentsand courts have integrated trauma-informed approaches.

- Homeless sheltersand the faith-based community are integrating practices based on ACEs research.

- Citiesand states are integrating ACE-, trauma-informed practices and resilience-building practices.

For an overview of ACEs, go to ACEs 101 – the FAQs.

Written By Jane Ellen Stevens

Aces Too High

Most Californians have experienced childhood trauma; early adversity a direct link to adult onset of chronic disease, depression, violence was originally published @ ACEs Too High » Jane Ellen Stevens and has been syndicated with permission.

Sources:

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts