Dr. Ramona Bishop in her office in a building that was once part of the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo, CA.

______________________

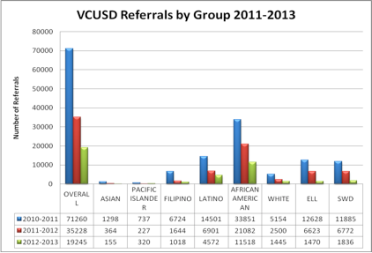

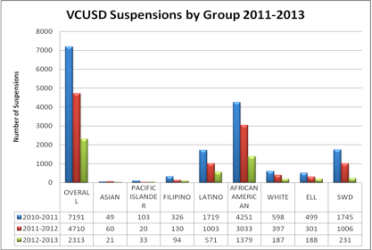

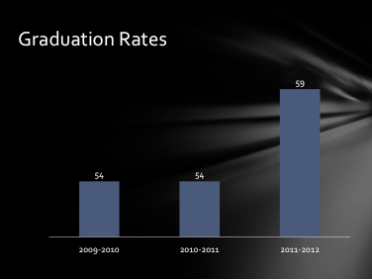

When Dr. Ramona Bishop walked into her office on April Fool’s Day in 2011, the Vallejo schools had hit rock-bottom: The system had been in receivership since 2004. Its 14,000 students were racking up nearly 80,000 referrals, suspensions, and expulsions that school year, making it one of the top-ten suspending schools in the state. Academic scores had tanked. Only half the students were making it to graduation. And morale? What morale?

The City of Vallejo had just dragged itself out of a 2008 bankruptcy resulting from the double whammy of the housing bubble and the 1996 closing of the Mare Island Naval Shipyard. It emerged emaciated, with all services cut to the bone.

Bishop couldn’t have asked for a more challenging job.

But this woman likes doing turn-arounds. She did one on a smaller scale when she was principal

of Bret Harte Elementary School in Sacramento. That took five years. To turn around a whole system? That’ll take seven years, she says.

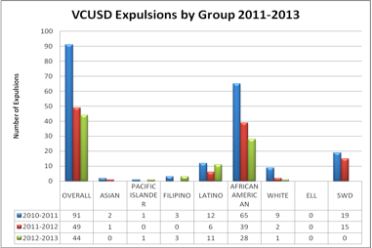

One-third of the way through the process, things are already looking up: Since the 2010-2011 school year, referrals have plummeted 75 percent. Suspensions dropped nearly 70 percent. Expulsions are down by 50 percent. Graduation rates are inching up from the 50-percent dropout rate. When she arrived, the system was losing 500 students a year, because parents were removing their children. This year, the system lost only 100 students, and Bishop expects an increase next year. In April, nine years after it went into receivership, the Vallejo Unified School district regained control of its schools.

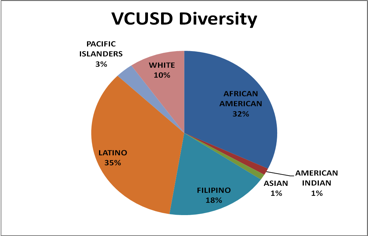

And they have a long way to go: The numbers of referrals, suspensions and expulsions still total more than the numbers of students in the system. African-American students still make up more than half the referrals, suspensions and expulsions, even though they’re only 32 percent of the student population. Academic scores haven’t increased; during the last school year, they dipped or remained stagnant.

But the foundation to support a successful and sustainable transition is nearly in place, says Bishop. The way she describes the process, it’s better visualized as a foundation that provides all the necessary elements for growth, as in gardening or agronomy, instead of construction. She and her co-workers in the Vallejo school system are not so much fabricating a building as laying down a rich layer of earth, and sorting out the right combination of nutrients, sunlight, and water so that children bloom and are never, ever lost again.

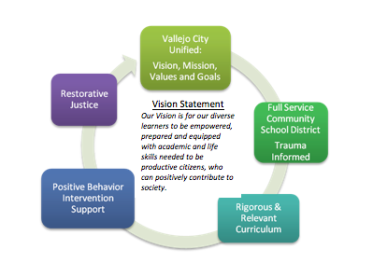

If there’s a road map for a system of successful schools these days, says Bishop – one in which no student is expelled or suspended, and all students are educated, it includes these elements:

- leaders who are strong, teachers and staff who are engaged, a committed community, involved parents, all of whom agree on common goals;

- solid academics;

- and a combination of the implementation of a system of trauma- and resilience-informed practices, positive behavioral support, such as PBIS, and restorative practices based on restorative justice.

Although the details of the road map will vary from school to school, says Bishop, the basic belief that underlies such a road map is this: There is no such thing as an uneducable child.

“We educate all children,” says Bishop. She hesitates.

“All means all,” she says firmly, but quietly. A useful way to interpret that is: “ALL MEANS ALL!!!!” shouted from the rooftop of every school in the district.

Here’s a conversation Bishop and I had about the transition in the Vallejo Unified School District.

Q: Where do you start when a school system has so many things going wrong?

Bishop: The city was poised and ready for change. We invited the community to the school board meetings and turned them into listening sessions. We showed the community the school discipline data, and asked for their ideas. At every school, we sent very intense surveys to parents, staff, leadership, and students, if it was a secondary school. Out of that, we worked with the community to develop our vision, mission, values and goals. The board approved them. That was our start.

Here, a group of amazing adults is working very hard in a system that needed a leader to come in and put systems in place, so that people could work toward the same goal. We’re on fire now. We have to do a lot of things simultaneously.

Q: It’s been 2.5 years since you began this transition. Where do things stand?

Bishop: We’re in the third year of PBIS implementation. [Positive Behavioral Intervention and Support, a classroom and school-wide system focused on encouraging and supporting students by acknowledging and rewarding their good behavior instead of calling out only their bad behavior.] We’ve seen significant changes in referrals and suspensions. Expulsions are about even. The amount of time students spend in class is increased. We’re not seeing changes in disproportionality yet [the fact that African-Americans are referred, suspended and expelled at a higher rate than is indicated by their percentage of the student body].

PBIS addresses the whole system. With the phase-in of restorative justice, which is expanding to 10 more schools this year, we’ll be able to address the disproportionality. [Restorative justice in schools is a system in which teachers and students develop written respect agreements. If a student – or a teacher – violates that respect agreement and the people involved cannot resolve the issue quickly, i.e., agree that the behavior is inappropriate, apologize, and return to adhering to the agreement, then they work out the disagreement with the help of a mediator, who often imposes consequences for the person who violated the agreement. The process is meant to resolve the situation peacefully, have the violator accept responsibility for her or his actions, and, through the consequences, learn from the incident.]

We have five full-service community schools. [In addition to academics and sports, full-service community schools provide health, mental health and social services – and any other services the community indicates it needs, such as food — for students and their families.] This year, we’re adding 10 more. Next year all the district’s 22 schools will be full-service community schools. When we implement full service, that’s when we bring in restorative justice.

We’re in the final round for a $400,000 Sierra Health Foundation Positive Youth Justice Initiative grant. [The foundation will announce the winners in January.] We’ll use it to infuse trauma-informed practices. This will bring a number of other agencies – foster care, juvenile justice, child welfare — around the table to focus on helping kids. Every staff member who has anything to do with a student will receive professional development around how our system will become a trauma-informed school system.

Q: The Positive Youth Justice Initiative addresses “crossover” youth – those that are involved with the juvenile justice system and who are in foster care. How many “crossover” youth are in the Vallejo schools?

Bishop: There are 121 students, district-wide, who are foster children and also in the juvenile justice system. Because we’re interested in eradicating the school-to-prison pipeline, we’ve broadened the definition of what a crossover youth is. That’s why we’re building support structures. So, instead of waiting until a student becomes a foster youth or becomes involved in the juvenile justice system, we will include any student at their first suspension, no matter what age.

Q: That’s interesting, because some research done in Pierce County, WA, juvenile justice system found that youth who experienced the most trauma in their childhoods received their first suspension at age 8 or younger.

Bishop: This is one of the things that the board asked me right at the beginning. At the age of six or seven, kids start reaching out to us for help, just by their behavior. And because our reaction has been to refer or suspend, 10 years later, we’ve got a kid who does something expellable. We’re organizing ways to share information so that all children who need help are helped. The United Way is providing funding so that data can be shared among different agencies and systems. By having systems talk with one another, we’ll be able to stop the confusion about how to help these kids. Foster parents, for example, won’t need to go to several agencies for help; they’ll just come to their child’s school.

Q: In what other ways are you supporting social/emotional health?

Bishop: We were awarded a Project Restore grant [from the U.S. Department of Education Elementary and Secondary School Counseling Program], which provides $1.2 million over 3 years. We’ll hire two social workers and two counselors who will focus on early intervention in five schools.

In our partnership with Kaiser’s Vallejo Medical Center, we’ll have six residents working in our full service community schools. They’ll have been trained in trauma-informed practices. By the beginning of the 2015-2016 school year, we’ll have 18 Kaiser residents.

And then we’re establishing a new position at every school. It’s an academic support provider. This person will act as the principal’s partner in dealing with the social and emotional health of students. The funding is coming from the California Department of Education’s Local Control Funding Formula.

This person will be the school service liaison at the school. They’ll work with the school district, Kaiser, United Way, and the county’s probation, mental health and child welfare departments. They’ll focus on the needs of that particular school and community, and build a collaborative at that school. They’ll make sure that parents are connected to the parent university. They’ll coordinate all student study teams, which are organized to do early intervention with students who are having problems.

Q: Why did the academic scores take a dip last year? Were you expecting that?

Bishop: As we looked at our STAR data this year [California Standardized Testing and Reporting], they took a slight dip in elementary and middle schools, while performance remained stagnant in secondary and certain subgroups. There was a slight dip in attendance, but increases in in-school time. I thought we would have an increase in STAR this year. It shows we’re not finished yet.

What we’re implementing is a belief system. As a belief system, this full-service approach has to kick in with the adults. I’ve always known that it’s not the kids or the parents, it’s us in the school system who have to change. The parents and students are easy; they’re ready. Some people have been part of a system that doesn’t believe we can educate all children. I hear people say: “What do you mean you’re going to educate all kids? This kid is uneducable. Kick him out.” Part of the change of this belief system, is that all means all.

Some of those people have moved away from the system. It’s allowing us to hire almost 100 new teachers this year. These new teachers believe that ‘all means all’, and if they don’t have the tool kit to do that, they say, “Point me to it.”

We know that we need to do something systemically to support those new teachers, so we’ve implemented a beginning teachers support system, based on the ideas of Dr. Jeff Duncan Andrade, so that we can build that full-service mindset for all of our teachers and administrators.

Q. You’re gathering data at every point possible in the schools — why is data-gathering important in administering all these new systems?

Bishop: I’ll give you an example. At Bret Harte Elementary [in Sacramento, where Bishop was principal], just before we had our leap, we had a dip. We had a group of English learners, the majority of which were Spanish speaking. At Bret Harte, the tests showed a 40-point drop in our white subgroup. To find out why, we looked at every student in our white subgroup. Turns out that half of them were Bosnian and Russian immigrants. The data forced us to look completely differently at how to help our English learners. We had an English learner advisory committee, but we were missing a group of families that needed to be involved.

This is an example of another reason I say that the road map will be different for each school. Every school serves a different community, with its own characteristics and set of needs. And we have to be aware of and fulfill those needs.

Q: How do you make this sustainable?

Bishop: This is a top-down and bottom-up approach, one that allows for the needs of our community to be met. It goes back to the mission, vision, values and goals that the community set at the beginning of this process. What will come out of it will be a superintendent-proof system that will continue regardless of who sits in my seat. I think if we tried to remove some of this work that we’ve implemented, the community would have some concerns.

Q: Does everyone in the community understand the need for this investment of time and resources?

Bishop: We get why it’s important for all students to be successful in school. Explaining that to city and county leaders, that’s where it becomes questionable. I hope what we’re doing is reaching those other audiences. At the end of the day, it’s not until we penetrate the thought process of leaders in the community to get them to understand why it’s important to give kids a second chance. That they can make their communities healthier by giving kids a second chance. That they can reduce crime rates and unemployment rates by giving kids a second chance.

Written By Jane Stevens

Aces Too High

This article has been syndicated with permission and was originally published @ http://acestoohigh.com/2013/10/24/vallejoschools/.

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts