When I was a child growing up in Kentucky, my father made regular visits − usually at night − to the local jail to provide medical care to inmates. In one way or another, substances were the root cause of both their illnesses and their incarceration. My teetotaler father had other gritty experiences with alcohol, finding himself from a young age getting his beloved “Uncle Ed” out of the drunk tank over and over again.

When I was a child growing up in Kentucky, my father made regular visits − usually at night − to the local jail to provide medical care to inmates. In one way or another, substances were the root cause of both their illnesses and their incarceration. My teetotaler father had other gritty experiences with alcohol, finding himself from a young age getting his beloved “Uncle Ed” out of the drunk tank over and over again.

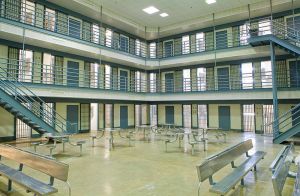

Elements of these recollections from the 1950s and 60s are as universal today as ever — the impact of substance abuse on the individual, the ripple effect of addiction and incarceration on the family, imprisonment instead of treatment — but the explosion in the rates of incarceration in this country have created a crisis of proportions unthinkable in the post-WWII era. According to the Pew Charitable Trust report, Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility, there are now 2.3 million Americans behind bars, equaling 1 in 100 adults, an increase from 500,000 in 1980. As we have heard from U.S. Attorney General Eric H. Holder in his speech in San Francisco on August 12, America has 5 percent of the world’s population but we incarcerate almost a quarter of the world’s prisoners. He described widespread incarceration as imposing a significant economic cost at local, state and federal levels — totaling $80 billion in 2010 alone — that comes with “human and moral costs that are impossible to calculate.”

In the context of ACE (adverse childhood experiences) research, the number of children who have a parent behind bars is especially relevant.  The Pew report finds the number of children with an incarcerated parent is now 1 in every 28 children compared to 1 in 125 just 25 years ago. Based on the large number of incarcerated individuals with both substance abuse problems and mental illnesses, the ACE scores of their children are approaching dangerous levels on these factors alone. The Pew report documents the collateral costs of locking up millions of people on their ability to regain even a portion of their economic viability and on the futures of their children. The children of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated parents share the resulting economic hardship and also have less of their own future economic mobility, lower educational achievement and are more likely to be expelled or suspended from school.

The Pew report finds the number of children with an incarcerated parent is now 1 in every 28 children compared to 1 in 125 just 25 years ago. Based on the large number of incarcerated individuals with both substance abuse problems and mental illnesses, the ACE scores of their children are approaching dangerous levels on these factors alone. The Pew report documents the collateral costs of locking up millions of people on their ability to regain even a portion of their economic viability and on the futures of their children. The children of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated parents share the resulting economic hardship and also have less of their own future economic mobility, lower educational achievement and are more likely to be expelled or suspended from school.

There was a hopeful and even elated response to Attorney General Holder’s announcement of steps being taken to reduce incarceration rates. Reducing incarceration and recidivism have galvanized leaders in both parties at the federal as well as the state level. Significant reforms have already been made in conservative states such as Texas and Kentucky, and serious discussions are underway in Congress by both Democrats and Republicans. But as Vanita Gupta points out in his NY Times op-ed of July 15, “How to Really End Mass Incarceration,” the impact of the Attorney General’s directives will be minimal (federal inmates account for just 14 percent of prisoners), and the work ahead to dismantle the “prison-industrial complex” is daunting, but achievable. Gupta recommends sweeping reform of the criminal justice system: eliminating mandatory minimum sentences, rescinding three-strikes laws, amending “truth in sentencing” statues that prohibit early release for good behavior, and decriminalizing marijuana possession. He also emphasizes, as does the Attorney General, the need for enhanced substance abuse prevention and treatment.

Commentary has been less focused on the other pressing need: to replenish the resources devoted to community mental health that have dwindled since state budget crises began with the 2008 economic downturn. Providing a fresh and unique voice on prison reform, Piper Kerman, the Smith College-educated former inmate at the Federal Connectional Institution in Danbury, CT. whose memoir is the basis of a new Netflix series called “Orange is the New Black,” points out that diminished mental health resources have resulted in women being imprisoned who simply do not belong there. In the August 13, 2013 op-ed “For Women, a Second Sentence,” she poignantly describes how important and mutual the relationship is between incarcerated mothers and their children, and suggests an alternative to incarceration through a promising program, JusticeHome, to keep mothers and children together, foster rehabilitation, and save money.

But the Council of State Governments (CSG) has quietly done the sustained work over more than a decade to find alternatives to incarceration especially for people with mental illness. Through technical assistance, research, and advocacy, the CSG Justice Center has addressed victim rights, criminal justice/mental health collaboration and prisoner reentry. The Center takes “a data-driven approach to reduce corrections spending and reinvest in strategies that can reduce crime and strengthen neighborhoods.” It is especially focused in areas where the criminal justice system intersects with other disciplines. Its work spans training judges to respond to mental illness to finding new approaches to school discipline.

In a recent NPR interview on “Here and Now” about Kentucky’s successful reforms to reduce the prison population and save millions, the state’s Secretary of Justice and Public Safety, J. Michael Brown, said they maintained their political will while being taunted as “hug a thug” soft-on-crime weaklings, but the hard part is left to do. He said, “We have to break the cycle of incarceration by developing substance abuse prevention and treatment programs since we know that approximately 75 percent of the prison population has a drug-related problem.”

ACEs-based approaches give us tools to recognize where risk factors exist — including but not limited to substance abuse and mental illness — and do something about them.

Written By Elizabeth Prewitt

ACEsConnection.com

Elizabeth Prewitt is a policy analyst for ACEsConnection.com, the companion community of practice (a type of social network) to ACEsTooHigh. She served as director of government relations and public policy for the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) from 2006 to 2011. She was the organization’s principal representative on Capitol Hill and liaison with federal agencies for the states’ mental health authorities.

Reduce ACEs by dismantling the “prison industrial complex was originally publish on Aces Too High and has been syndicated with permission.

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts