How is the world real? What is its composition? Is it found or created? What are its limits? What is the connection between our behavior and our world(s)?

The early Wittgenstein and the late Peter Ossorio worked it out this way. They said a lot more, but this is a good place to start:

1. The world is everything that is the case.

1.1 The world is the totality of facts, not of things.

1.11 The world is determined by the facts, and by these being all the facts.

1.12 The totality of facts determines both what is the case, and what is not the case.

1.13 The facts in logical space are the world.

1.2 The world divides into facts.

1.21 Something can be the case or not be the case while everything else remains the same.

2. What is the case-a fact-is the existence of a state of affairs.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 1922

A1. A person requires a world in order to have the possibility of engaging in any behavior at all.

A2. A person requires that the world be one way rather than another in order for him to behave in one way rather than another.

A3. A person’s circumstances provide reasons and opportunities to engage in one behavior rather than another.

A4. For a given person, the real world is the one which includes him as a Person, and as an Actor, Observer-Describer, and Critic.

A5. What a person takes to be real is what he is prepared to act on.

A6. A person acquires knowledge of the world by observation and thought.

A7. For a given person, the real world is the one he has to find out about by observation.

A8. A person takes it that things are as they seem unless he has reason enough to think otherwise.

A9. A person takes the world to be as he has found it to be.

also keep in mind:

D11. The world is subject to reformulation by persons.

Peter G Ossorio, Place, 1998

and about knowledge:

Information is a difference that makes a difference.

Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 1972

Descriptive Psychology’s concept of World consists of the concepts and facts concerning the Objects, Processes, Events and States of Affairs (OPESAs) that have a place in Behavior. These are the distinctions, the elements, we act on. I have a telephone (an object) that starts (an event) ringing and goes to voicemail (a process) that I avoid (a state of affairs). All of this is real.

No single element of the OPESA is enough to make up a World. The entire package and the relationships are required. Relationships and elements that have a place in behavior are all essential aspects of the World, mine or anyone’s. Descriptive Psychologists are not alone in thinking this way. We are in the large company of pragmatists.

In A Short Course in Descriptive Psychology, I provide a brief introduction to the Person Concept: the interrelated, interdependent concept that links together the meaning of Individual Person, Behavior, Language, and World. In that entry, I say a bit about individual persons and behavior. In Language, Influence and Self-Presentation, I write about language as symbolic verbal behavior; something always involving social practices framed by the participants’ status as appraised by actor and observer.

Here are remarks about the Descriptive concept of World and Reality and its empirical manifestation as a person’s Real World.

The concepts of world and behavior are interdependent since meaningful distinctions are those that can, in some manner, be acted on. In this way, the world is a social construction. Social constructions are neither random nor arbitrary since they are bounded by the possibility of effective action. The limits of the world are the limits of behavior. The limits of behavior are the limits of the world.

Descriptive Psychology recognizes the distinction between everything that is actually the case in contrast to what could possibly be the case (in this or any other world). The limits on the possible are boundary conditions. The Real World is the single whole that contains a place for the person (as Actor, Observer, and Critic) and all that is in that whole, no matter how large or small. Reality, on the other hand, is used to refer to what worlds could possibly be the case given the boundary conditions. Here’s a kicker: we can’t possibly know all those boundary conditions. As Ossorio put it, “We have limitations. And one of our limitations is that we don’t know our limitations.”

Descriptive Psychology is essentially pragmatic. Not just anything goes. The distinctions that make up a person’s world must be useful, must make a difference in behaving one way or another. If you distinguish X from Y, but I can’t in any way employ X differently than Y, then, at least for me, there is no practical difference between X and Y. Making and acting on distinctions requires sensitivity and competence. Some people are in a better position to notice and act on a difference. Perhaps you can see it but I can’t.

The different ways a person can act on X and Y is the informational value of X and Y.

A person’s Real World is the full set of empirical or historical elements (OPESAs) that informs their Behavior Potential. This includes the possible elements they might consider, imagine, discover or invent. Considering or imagining might not result in discovery or invention. Ideas often don’t pan out, but still have the status of a wondering. What we wonder, practical or not, matters to us. Still, since action is key to meaning, competence and effectiveness are fundamental in evaluating a person’s knowledge. This is reality testing. Knowledge is vindicated by the action it facilitates. Knowledge of the world requires that we are in a position to look around, think, and act.

This pragmatic point of view is less focused on truth and more by a concern with effectiveness and competence. (“I don’t care so much that you say it’s true. What I want to know is can it get you three in a row?” or perhaps, “The proof is in the pudding.”)

As an overarching guide to behavior, Cultures, by framing ways of life, define their member’s shared worlds. As cultures change, the world of its members change accordingly.

Every world is someone’s world. No one’s world exists in solipsistic isolation. Meanings are created publicly, through social practice. Worlds, like languages, have the logical requirement of the potential to be shared. But since effective action requires knowledge and competence, not every world is completely sharable with everyone. A person has to be in an appropriate position, must have the requisite status, to engage in the actions that validate a world. Without the necessary math, I remain blind to the world of physics. Without some sense of soul, I am numb to the experience of the spirit.

These distinctions are embodied in the Descriptive concept of Status. A person’s status is their place in the world. Here, status means more than a conventional concern with rank and prestige, although these notions are features of a person’s overall status. At different times, under varied circumstances, some aspects of a person’s status are more relevant than others. Consider the sergeant who directs the march in lockstep, but looks like she’s herding kittens when she attempts to get her kids up and ready for school (although you’d not be surprised to see something similar in the way she does both).

The Descriptive concept of status bears resemblance to the ecological notion of niche formulated by G. Evelyn Hutchinson. Hutchinson’s niche is an “n-dimensional hyper-volume” consisting of all of the relevant resources and environmental circumstances relevant to an organism’s way of life. Peter Ossorio’s “status” and Hutchinson’s “niche” define the boundaries of a real world. They both concern behavioral context, possibility, and constraint.

Consider, the etymology of the word “world” comes from the Old English “worold” roughly meaning “the age of man”, “a long time” or “the course of one’s life”. The world is what we find and create in living our life.

What we find, what constitutes and becomes our world, follows from our personal characteristics and circumstances, our place. This, in turn, may alter our personal characteristics as our relationships change, accordingly. In Ossorio’s 1976 lectures on Personality and Personality Theory, Peter talks about status and the relationship of a person to his world while addressing the question of where our behavior potential comes from. He had just finished talking about the Relationship Formula, having said elsewhere: “It has been perfectly clear to most people most of the time that human behavior is a function of a person’s relationships and of a person’s place in the scheme of things” (Behavior of Persons, 2013).

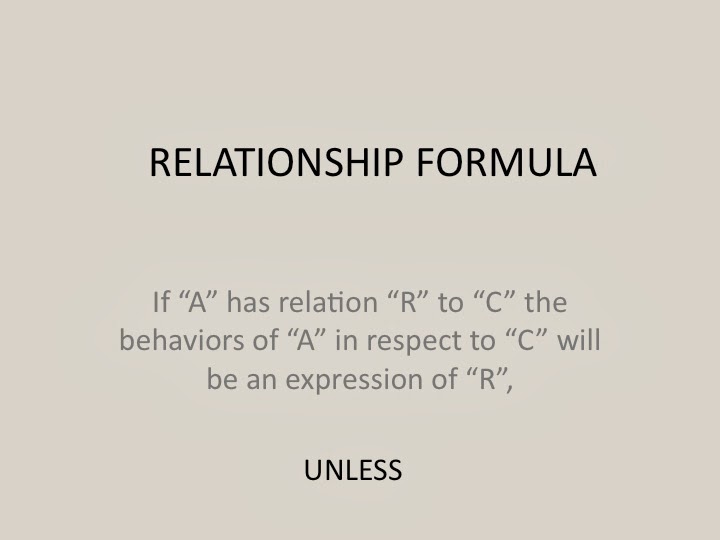

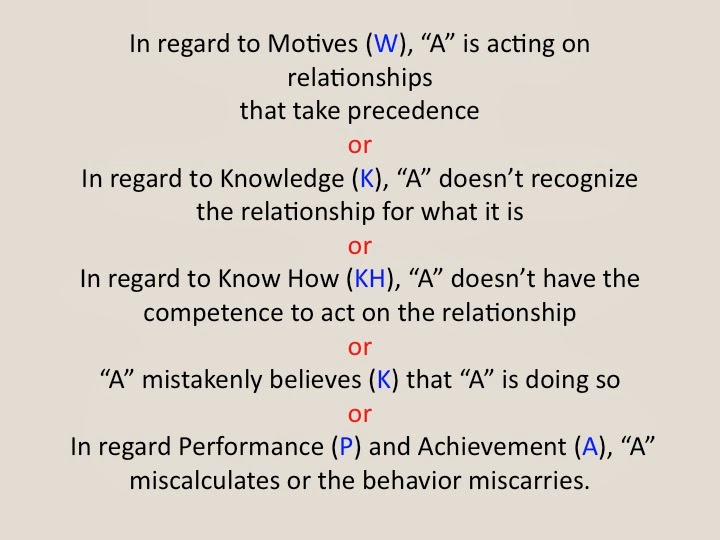

The Relationship Formula sets out the logic of what a person acts on: “A person will do X unless…”. Unless clauses are particularly important.

Ossorio also provides rules for the Reality Game. In the The Behavior of Persons, he defines the basic reality concepts and provides transition rules for their composition and interrelations.

Joe Jeffrey summed it up for me this way, “What kinds of things are there in the world? Objects, processes, events, and states of affairs. Everything you ever see in the world, as you look around you, will be one of those. What are concepts? Distinctions people can act on.”

And that’s the whole kit and caboodle.

And how does the world seem? Greg Colvin tells this story: After my first undergraduate class with Pete, he left on sabbatical and I was left trying to make sense of What Actually Happens, sitting for hours in the library where the single manuscript was available. When Pete returned I told him, “I just don’t get this Reality concept. And of course he said, “Let’s take a walk.” All I recall of the walk is him taking a pencil and asking me, “What is this?”

“I dunno, two pieces of wood pressed around a graphite core, rubber and a metal band to hold it together.”

“It’s a pencil, damn it.”

I try to make sense of what it is to be satisfied with one’s world in Satisfaction, Narcissism, and the Construction of Worlds.

The Person Concept and the its components, Individual Person, Behavior, Language, and World, is explicated in Peter Ossorio’s (2013) The Behavior of Persons. The 2013 paperback includes C.J. Stone’s index, not found in the 2006 hardbound edition. The State of Affairs System and transition rules are found and elaborated there.

Ossorio has written about the problems with traditional Ontology and further elaborated the State of Affairs System in his 1996, “What there is, How things are” .

Special thanks to C.J. Stone, Joe Jeffrey and Greg Colvin for their help in refining my understanding of these concepts. C.J. reminded me of Ossorio’s statements in Personality and Personality Theories.

Written By Wynn Schwartz Ph.D

What is Reality? was originally published @ Lessons in Psychology: Freedom, Liberation, and Reaction and has been syndicated with permission.

Sources:

Our authors want to hear from you! Click to leave a comment

Related Posts